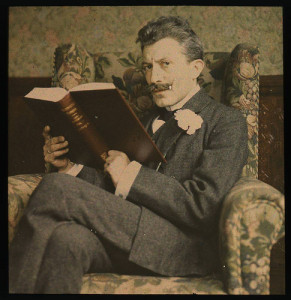

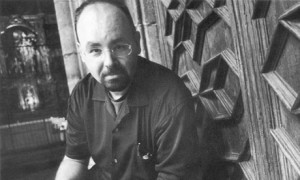

On Monday I popped along to the Wheeler Centre to see Barcelona-born, LA-based author Carlos Ruiz Zafón in conversation with local writer and broadcaster Sian Prior. As usual, I went bearing pen and paper, and took copious notes. (A video of the event will be forthcoming from the Wheeler Centre, but a sort-of-verbatim transcript never hurts.)

Prior began the conversation with an observation regarding Ruiz Zafón’s obvious passion for books as artefacts, as well as the power of stories, and how these appear as recurring motifs in his work.

Stories have always been an important part of Ruiz Zafón’s life: even as a child he was fascinated by the concept of storytelling, and by all types of stories, between which he never differentiated as a young reader. Everything was, to him, a “big bag of stories”. He was intrigued not just by stories, but by their structure and architecture, and was always toying with them and analysing them to determine how they worked. It was only later that he began to differentiate between different forms of storytelling–for example between books, graphic novels, and films–as well as the different genres within these forms.

As seems to be surprisingly often the case for bookish individuals, Ruiz Zafón was the only keen reader in a family that was generally not especially interested in the arts and entertainment. As such, he was always seeking out books wherever he could find them, an approach to which he partly contributes his omnivorous reading diet. He would read through his father’s book collection, which comprised large sets of beautifully bound, poorly printed classics and heavy books–the types of books bought for display rather than for reading, and which Ruiz Zafón joked were probably bought by the metre. In addition to these, he would also read the Marvel comic books that his grandmother would buy for him.

A book is a gothic cathedral of words.

Prior commented that this kind of genre agnosticism is evident in Ruiz Zafón’s own work, which mixes genres and stylistic elements in a way that is redolent of a labyrinth.

Ruiz Zafón agreed, saying that he relishes working with complex, challenging systems and developing labyrinthine, layered works. His approach to plotting is one that takes time to coalesce into something concrete, involving as it does a good deal of time spent on thinking and musing over various themes, elements and characters and the way that they will overlap. It’s also one that requires re-plotting and re-working: no matter how much time is spent on developing these things, everything needs to be continually redrawn as the book progresses.

It’s a system that has evolved over time, however. When he first started out, he tended to work without much of a plan, and would let himself reach the end of a work before going back to fix problems or analyse the devices he had incorporated. Now, however, he thinks of plotting a book as something akin to building a gothic cathedral–a complex structure made from words. It’s essential to keep restructuring and reworking until the final result is as close as possible to the original idea.

A good deal of planning was required when developing the four-book Shadow of the Wind cycle, which he originally conceived of as a single, epic volume. Having got about thirty or pages into the manuscript of the first volume, he realised that the result would be something so monstrous that it would probably be physically impossible to shelve it (and, he joked, there was the risk that people might perish under the weight of the thing). He didn’t, however, want to write the cycle as a sequential series or 19th Century-style saga, but rather as four books, each representing a different entry into the “labyrinth” of an overarching narrative, and thus creating a variety of different possible reading experiences.

The aim was to deconstruct storytelling, to play around with it, and to make storytelling itself the heart of the story: he wanted to explore readers’ often complex relationships with books, how genres and so on work, and to combine it all using whatever tricks were available to him as an author. All of this was pinned against the skeleton of the classic saga trope of a young boy growing up and trying to find his place in the world.

Ruiz Zafón believes firmly that character should always usurp plot, and that good plots arise from good characters, not the other way around. Each of the characters in The Shadow of the Wind saga has a variety of roles to play. Fermín, for example, is an homage to the picaresque tradition. He’s the fool, the madman, the jester, but at the same time, has the freedom to speak the truth when no one else can. He’s the moral centre of the books even though he’s not necessarily going to be taken seriously by the reader due to his strange and outlandish theories. But these are theories and are always well-meant: he always attempts to be a decent person in a profoundly decent world, something at which all of the other characters eventually fail.

To destroy books is to destroy the mind.

Prior suggested that in the books there’s a sense of books and reading being in a way dangerous, and Ruiz Zafón concurred, saying that books and knowledge can be a curse for some. You can fall in love with literature, he said, but literature never falls in love with you. He added that books are a repository of beauty, knowledge, memory and identity, and that they help us understand who were are. It’s this power that makes them so very dangerous in the eyes of some–to the extent that some groups seek to destroy books, hoping that in doing so they can destroy all that books represent.

When you destroy language, you destroy identity. And to destroy books is to destroy the mind.

Prior commented on the connection between language, culture and place, and asked to what extent the cycle is an homage to Barcelona, a place with which tourists so famously fall in love. Ruiz Zafón responded that Barcelona is his mother, something so key to his identity and experience that he cannot see it in the way that a tourist does. Rather, he seeks to get to the true heart of the city, to explore the truths of its characters. He has a conflicted relationship with the city, seeing it as he does through the eyes of a native, but like all writers he needs to engage with it in order to come to terms with his roots and origins. He is, though, very aware that it’s impossible to portray a city exactly as it is: there are many Barcelonas.

When asked about both the difficult history of Barcelona and the research that goes into his books, Ruiz Zafón responded by saying that he believes that most residents of the city today don’t necessarily think, at least deliberately and consciously, of events such as the civil war or WWII, and that they’re disconnected from the past in a way, having not been alive during those times. He says that this is something that’s true for all of Europe: “The end of the world happened there sixty years ago, but now it’s all Benetton shops.”

However, even so, it’s impossible to escape the history of a place. As someone who’s a natural autodidact, he’s always seeking to learn more about his home city, and about the world generally. Rather than researching something specifically, for specific purposes, he tends to simply read widely and supplement this reading with his own deep knowledge of specific things. He would not write about something about which he’d need to begin from scratch–for example, he would be shy writing about Melbourne as not only does he not know the city, he feels as though he could never know it.

Interestingly, the majority of The Shadow of the Wind cycle was not written in Barcelona, but rather in Los Angeles, where Ruiz Zafón prefers to write, believing that he is more productive and creative there. The Angel’s Game, however, was written in Barcelona, and he believes that it shows: place inevitably taints the writing. He feels, too, that the books are not at all Spanish in feel–even the Barcelona of the books is very much a construct–but rather have a very LA-style sensibility, something that was an issue when he attempted to sell the books into Spain, which saw them as entirely “un-Spanish” and outside the Spanish literary tradition. It wasn’t until the books become hugely successful that they were gradually accepted into the Spanish literary scene.

Young readers are sincere and passionate, but they’re also merciless.

Prior drew the conversation around to matters of audience, noting that although Ruiz Zafón’s first few books were for young readers he seems to write now for an audience that’s more adult-oriented, or that at least has crossover appeal. Ruiz Zafón rather sheepishly explained that he found himself writing for young readers after his first book won a prestigious YA award that came with a large monetary prize. He was all too aware of how difficult it was to make a living as an author, and so felt in a way that he had to pursue this path, even though in his heart he had never wanted to write within a specific genre or for a carefully delineated audience. Perhaps out of conservatism or cowardliness he continued writing young adult books until he realised that he was betraying not only himself, but his readers by doing so.

He noted, though, that when he first began writing for young readers, the market was nothing like how it is now: there was no internet, and no young adult category. There were certainly no paranormal romance shelves, he said, lamenting about such books, “man, it’s the end of the world. We have like six months.” However, though YA isn’t his genre as such, he believes that young readers can be among the best readers an author can have. They’re sincere and passionate, but they’re also merciless. Unlike adult readers, they can’t be swayed by reviews or awards, and will put down a book immediately if it doesn’t grab them.

The conversation steered around to the place of the bookshop in today’s world, something that is of interest to Ruiz Zafón given the subject matter of his books. When Prior suggested that we might be seeing the “end” of the bookshop, Ruiz Zafón disagreed, arguing that although many of today’s bookshops will disappear, others will appear. The problem is, he says, we have a habit of thinking of ourselves as the end of history, when really we’re merely passing through. Everything changes, and will change even in our lifetimes. Publishing, for example, has changed dramatically over the past century, and what we think of as “publishing” or “bookselling” is really only a brief moment of transition in a changing model.

Beauty and knowledge – the redeemers.

Whether books, stories, or minds survive, however, is something that is up to us. Ruiz Zafón believes that there are two redeeming values in the world: beauty and knowledge.

Support Read in a Single Sitting by purchasing Carlos Ruiz Zafón’s books using one of the affiliate links below:

Amazon | Book Depository UK | Book Depository USA | Booktopia

or support your local independent.

Books by Carlos Ruiz Zafón:

The post Event Summary: Carlos Ruiz Zafón in conversation at the Wheeler Centre appeared first on Read in a Single Sitting - short books, page-turners, and books you can't put down.

]]>